Symmetry¶

A symmetry is a group of transformations in space. Each element of the symmetry group is represented as a transform.

Coxeter groups

The symmetry groups of most puzzle shapes are Coxeter groups. It's highly recommended that you learn about Coxeter groups and their construction using mirror planes before reading the rest of this page. The section titled Symmetries of the cube in the excellent article Building 4D polytopes by Mikael Hvidtfeldt Christensen is a good primer, and the interactive demos with three planes are very helpful references.

Constructors¶

cd()¶

cd() constructs a Coxeter group. It takes two arguments: a Coxeter group description and an optional basis.

Coxeter group description¶

The Coxeter group description is either of the following:

- Table of branch labels. Calling

cd()with a table containing a sequence of positive integers constructs group corresponding to the linear Coxeter-Dynkin diagram with those branch labels. - Coxeter group name. Calling

cd()with the name of a Coxeter group constructs that Coxeter group. The name is case-insensitive and must consist of one or two letters followed by a number.

The table of branch labels is similar to a [Schläfli symbol]. For example, cd{4, 3} is the symmetry group of a cube, and is equivalent to cd'b3', cd'c3', and cd'bc3'.2

Here is a list of the names for the finite Coxeter groups:

a2,a3,a4, ... (simplical symmetries)bc2,bc3,bc4, ... (hypercubic symmetries)- equivalently:

b2,b3,b4, ... - equivalently:

c2,c3,c4, ...

- equivalently:

d4,d5,d6, ... (demicubic symmetries)e6,e7,e8f4(24-cell symmetry)g2(hexagonal symmetry)h2,h3,h4(pentagonal, dodecahedral/icosahedral, and 120-cell/600-cell symmetries)i2,i3,i4, ... (polygonal symmetries)

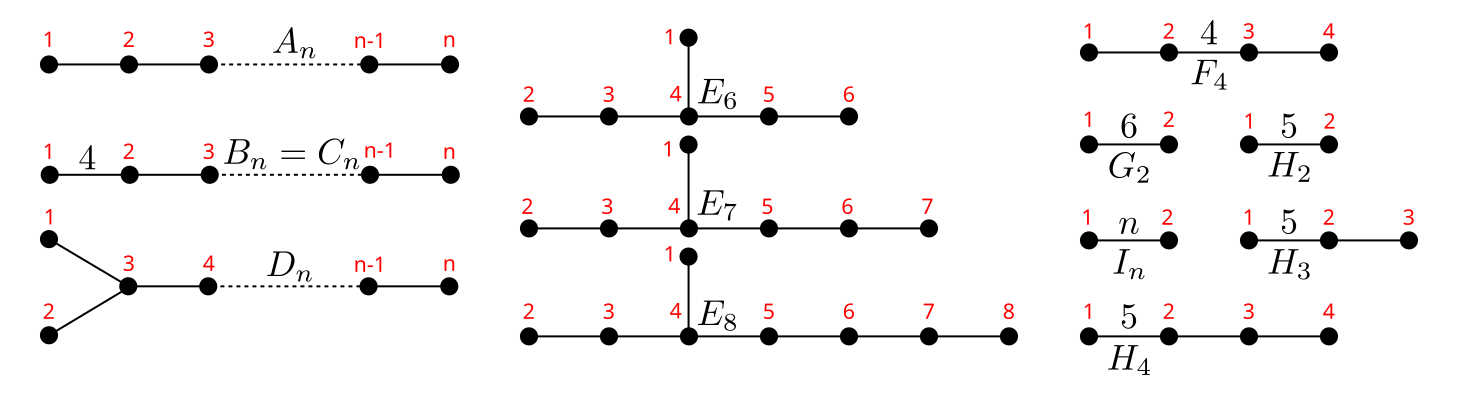

This diagram describes the Coxeter groups graphically, with labels representing the indices of the nodes in the program1:

Coxeter group basis¶

The basis for a Coxeter group may be specified as a string of axis names (such as 'yzw') or a table of vectors (such as {vec(1, 2), vec(-2, 1)}). In either case, the number of vectors specified must be equal to the number of mirrors in the Coxeter group. Vectors are normalized before constructing the Coxeter group so they do not need to be normalized, but they must all be nonzero and mutually perpendicular.

local sym

sym = cd'a5' -- pentagonal symmetry in the XY plane (first mirror is along X)

sym = cd{5} -- pentagonal symmetry in the XY plane (first mirror is along X)

sym = cd('a6', 'yz') -- hexagonal symmetry in YZ plane (first mirror is along Y)

sym = cd('a7', {vec(1, 2), vec(-2, 1)}) -- heptagonal symmetry in XY plane (first mirror is along `vec(1, 2)`)

sym = cd'bc3' -- cubic symmetry in the XYZ hyperplane (first mirror is along X)

sym = cd{4, 3} -- cubic symmetry in the XYZ hyperplane (first mirror is along X)

sym = cd('bc3', 'wyz') -- cubic symmetry in WYZ hyperplane (first mirror is along W)

symmetry()¶

symmetry() constructs a group from generators. It takes a single argument: a sequential table of generator transforms. Twists are automatically converted to transforms.

The fields .mirror_vectors, .chiral, and .is_chiral and the method :vec() are not supported on symmetries constructed using symmetry().

Fields¶

Symmetries have the following fields:

.ndimis the minimum number of dimensions required to contain the symmetry.mirror_vectorsis a table of vectors, each corresponding to one of the mirror transformations that together generate the group.chiralis the canonical chiral subgroup of the symmetry; i.e., the symmetry which is the same as this one but excluding reflections.is_chiralistrueif the symmetry is chiral (i.e., it does not contain any reflections), orfalseotherwise

local mirror_vectors = cd'bc3'.mirror_vectors

assert(#mirror_vectors == 3)

assert(mirror_vectors[1] == vec(1))

assert(mirror_vectors[2] == vec(-1, 1) / sqrt(2))

assert(mirror_vectors[3] == vec(0, -1, 1) / sqrt(2))

Additionally, symmetries have a field corresponding to each possible vector written in Dynkin notation that uses only the characters o and x. For example cd'bc3'.xoo is a vector pointing toward the vertex of a cube or the face of an octahedron.

Methods¶

Symmetries have the following methods:

symmetry:orbit()¶

symmetry:orbit() returns the orbit of its arguments under the symmetry. See symmetry:orbit() for more.

symmetry:vec()¶

symmetry:vec() returns constructs a vector in the mirror basis, where each axis is parallel to all but one mirror. It can be called in either of two ways:

- Dynkin notation. Calling

:vec()with a Dynkin notation string constructs the corresponding vector. See Dynkin notation for an explanation and examples. - Vector. Calling

:vec()with an existing vector converts it to the mirror basis. The first component of the input determines the distance from the first mirror; the second component of the input determines the distance from the second mirror; etc.

symmetry:thru()¶

symmetry:thru() constructs a transformation by composing reflections across the corresponding mirror planes. Each mirror plane is specified as an index. First each reflection is constructed, and then they are composed in the order specified.

For example, symmetry:thru(1, 3, 2) constructs a transformation that reflects through the second mirror plane, then the third, then the first. Note that the order seems backwards, because the transforms are composed in the order written.

cd'bc3':thru(2, 1) -- clockwise 90-degree rotation of a face of a cube

cd'bc3':thru(3, 2) -- clockwise 120-degree rotation of a vertex of a cube

cd'bc3':thru(3, 1) -- clockwise 180-degree rotation of an edge of a cube

local sym = cd'bc3'

local a = sym:thru(1, 2, 3)

local b = sym:thru(1) * sym:thru(2) * sym:thru(3)

assert(a == b)

Operations¶

Symmetries support the following operations:

type(symmetry)returns'symmetry'tostring(symmetry)

Dynkin notation¶

To describe points relative to a symmetric mirror construction, we use Dynkin notation. A point specified in Dynkin notation consists of a string of characters, each specifying the distance from its corresponding mirror planes. Here is a list of all the symbols supported by Hyperspeedcube:

| Symbol | Distance |

|---|---|

o |

\(0\) |

x |

\(1\) |

u |

\(2\) |

q |

\(\sqrt 2\) |

f |

\(\phi = \frac{1 + \sqrt 5}{2}\) |

For example, the string oqx describes a point touching the first mirror plane, \(\sqrt 2\) units from the second mirror plane, and \(\phi\) units from the third mirror plane.

local sym = cd'h3' -- symmetry of a dodecahedron or icosahedron

sym:orbit(sym.oox.unit) -- face poles of a dodecahedron, or vertices of an icosahedron

sym:orbit(sym.oxo.unit) -- edge poles of a dodecahedron or icosahedron

sym:orbit(sym.xoo.unit) -- vertices of a dodecahedron or face poles of an icosahedron

local sym = cd'bc4' -- symmetry of a hypercube or 16-cell

sym:orbit(sym.ooox.unit) -- cell poles of a hypercube, or vertices of a 16-cell

sym:orbit(sym.ooxo.unit) -- face poles of a hypercube, or edge poles of a 16-cell

sym:orbit(sym.oxoo.unit) -- edge poles of a hypercube, or face poles of a 16-cell

sym:orbit(sym.xooo.unit) -- vertices of a hypercube, or cell poles of a 16-cell

-

Derived from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Finite_coxeter.svg ↩

-

Lua syntax allows omitting the parentheses when calling a function with a table literal or string literal as its only argument. For example, you can write

cd{4, 3}instead ofcd({4, 3})orcd'bc3'instead ofcd('bc3'). ↩